When a Room Becomes a Choir: Recording a Song Together at the Music Care Conference

There are conferences that inform, inspire, and educate, and then there are conferences that change how we imagine what care can feel like. The Music Care Conference: The Power of a Song in Dementia Care, held at Metalworks Institute in Mississauga, was one of those rare experiences. Positioned as a national gathering that brings together people engaged in music in care across clinical, community, and educational settings, the purpose of the day became clear right from the beginning. This was not a passive event; it was an active space for co-creation and genuine connection. From the moment participants arrived, the atmosphere felt more like the start of something being built together.

One of the most profound moments came during a workshop led by Bev Foster, where attendees from diverse backgrounds were to record a song together. There was no expectation of musical training or polished performance. The invitation was simply to contribute a voice and be part of the process. The piece we created was titled ‘Without a Song,’ written by Canadian singer songwriter Murray McLauchlan, and in that moment it became a shared expression of care and connection. What began as a room full of strangers gradually shifted into a connected musical space. People leaned in, listened closely, and began to sing together with growing confidence. It felt less like watching music happen and more like becoming part of something shared.

In that moment, the workshop no longer felt like a breakout session. It became a living example of care expressed through music. This experience carried particular meaning in the context of dementia care. When language shifts or memory becomes harder to access, music offers a different pathway to connection, one grounded in presence. Creating music together invites participation rather than observation and can restore a sense of agency for people whose autonomy is often limited by care environments. It also strengthens relationships between caregivers and the people they support. Music does not sit on the edges of care as an added activity. It can function as care itself.

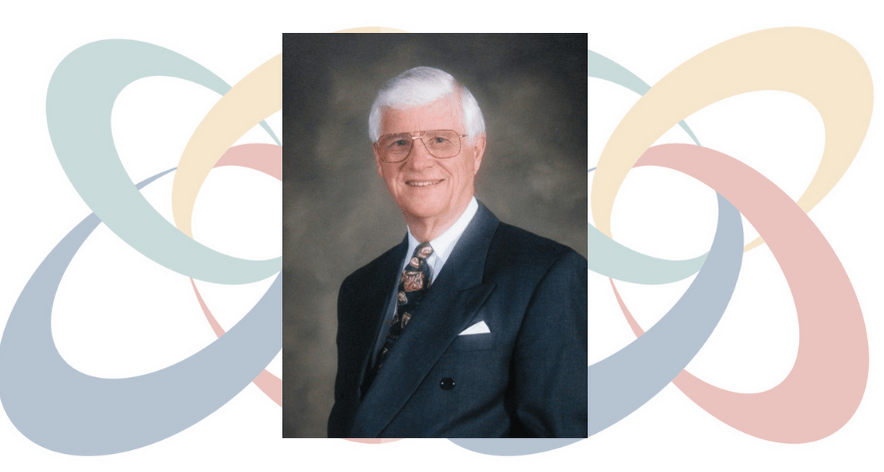

The conference also highlighted that the role of music in dementia care is part of a broader shift in how the sector is evolving. With growing momentum around Bill 121, the Improving Dementia Care in Ontario Act, and increased attention from the Ministry of Long-Term Care, music is beginning to be recognized as a meaningful part of care. This commitment was reflected in a heartfelt address from Minister of Long-Term Care, Natalia Kusendova-Bashta, whose remarks affirmed the importance of dignity and compassion in dementia support. At one point she held her son at the podium and led the room in a playful rendition of ‘Baby Shark’, a moment that demonstrated how music creates connection across generations and circumstances. Policy can outline goals, but experiences like this help us imagine what care feels like when creativity and connection guide the approach. Throughout the day, research and lived practice came together through presentations from experts such as Dr. Lee Bartel, Dr. Alison Sekuler and Taylor Kurta, and through examples from organizations already integrating music-based programs in long-term care and community settings.

Although the collaborative songwriting session stood out, it was one part of a day filled with meaningful experiences. The Raising Voices Dementia Choir demonstrated how music can help people living with dementia stay connected to their identity and to the people who support them. Later, the closing performance by Jill Barber brought a different dimension to the day, weaving artistry, memory, and personal storytelling into a musical experience that resonated deeply with the audience. The day also highlighted new models of community engagement such as the ‘Memories to Music’ songwriting project between the Alzheimer Society of Peel and students from Mentor College. Led by music teacher Ian Hoare and music therapist Ruth Watkiss, this initiative brings young people and persons living with dementia together to create original music, demonstrating how intergenerational collaboration can strengthen understanding and relationships across care settings.

As I left the conference, I kept returning to the responsibility that comes with making music together in a care context. The song we created did not end when the session wrapped up; it became a reminder of what can happen when care is grounded in creativity and shared voice. If a group of people with no prior relationship can come together and create a shared musical experience in such a short time, then there is potential to bring this same approach into long-term care homes, community programs, hospitals, and family caregiving settings. These environments are already spaces of deep commitment and compassion, and with the right intention and support, music can help deepen relationships and strengthen the culture of care.

The power of music in care is not found in adding it as a program feature; it comes from recognizing it as a way of relating to people with dignity and presence. When music becomes a shared experience, people living with dementia are included and understood rather than defined by their diagnosis. This work continues through collaborations with partners such as Acclaim Health, the Alzheimer Society of Peel, ArtsCare Mississauga, and Metalworks Institute, who help create environments where music supports meaningful connection.

The music eventually came to an end, yet the song stayed with me as more than a moment from the day. It became a reminder of what can happen when care is grounded in creativity and shared voice. I left the conference with a clearer sense of how music can shape the way we support one another in real and meaningful ways. As we look ahead to the next Music Care Conference in Halifax in 2026, we carry this momentum forward, knowing that none of it happens ‘without a song’ to bring us together.